Prototyping for Social Wellbeing with Early Social Media Users

Published in CHI 2021

Summary

This blog post summarizes a paper published by Linda Charmaraman and Catherine Grevet Delcourt at CHI 2021. This work presents a remote innovation workshop with 23 middle schoolers on digital wellbeing, identity exploration, and computational concepts related to social computing we conducted in summer 2020. Participants in this workshop reflected on emergent online habits, discussed them with peers, and imagined themselves ICT innovator. In this blog post we summarize the structure of our workshop, resulting discussion themes related to participants’ social wellbeing online, and the participatory design and testing of a social network website.

Introduction

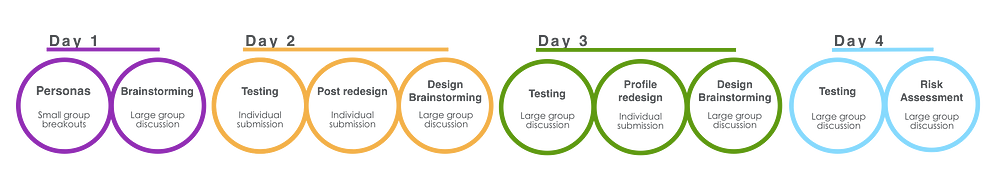

The early habits that young adolescents (10–14 years old) develop on social media can have lasting effects on their socio-emotional wellbeing. At an age when social processes are key to their development, social wellbeing is essential as they transition from their family unit to rely more on peer networks. Building a strong sense of belonging, learning empathy and their role as part of a larger community are key components of their social wellbeing. Informal educational opportunities to reflect and engage on topics of social wellbeing, in the context of ICTs, are limited for today’s youth. Our summer workshop with 23 middle school students took place remotely, over 4 days. We discussed topics relating to social wellbeing, identity, and computational concepts related to social media. Through this workshop, we engaged students in online activities, and together designed a social media website to support social wellbeing that we iterated on during the 4 days.

Our paper contributions are:

1) An account of online social wellbeing experienced by a group of middle school students during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

2) A description of activities for workshops with early social media users to explore social wellbeing.

3) An account of a social media prototype, called Social Sketch, resulting from an iterative design process focused on supporting social wellbeing.

Workshop Setup

Participants

Students came from 6 different middle schools across 3 states in 2 different time zones. They were 11 7th graders, 11 8th graders, and 1 9th grader, ranging in age from 12 to 14. The vast majority did not know each other beforehand. Our workshop students (13 females, 10 males) were also ethnically diverse.

Workshop Structure

Roles: The workshop was facilitated by the authors, a project coordinator, two high school students, and a recently graduated college senior. The research team structured the schedule, monitored the remote technologies (Zoom waiting rooms, Seesaw, etc.), and facilitate team building.

Development of Units: We focused our workshop on promoting social wellbeing and identity exploration. The curriculum had two axes: social units and technology units. For the social wellbeing units, we discussed a) coping with social distancing, b) positives and negatives of social media affordances, particularly on social interactions, c) enhancing personal awareness of social and emotional wellbeing online and offline, d) understanding the purposes of social media use in different social contexts, during different life stages, for various audiences, and e) reflecting on their use of YouTube and how they might identify with others emotionally. The technical units were on innovation, design processes, roles, and tools used in the development of social media apps; and involving students in industry activities.

Social Network Sandbox: A running activity through the 4 days of the workshop was prototyping a social network website. We call this a social network sandbox because it represented a bounded and safe space for participants in our workshop to try new ideas. The Social Network Sandbox contained the core components of social network sites: account authentication, editable user profile pages, a list of users of the page for graph traversal, and an activity feed of user-generated content.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted a pre- and post- study survey to analyze the impact of the workshop. We captured the audio transcript of the Zoom calls. We collected submissions created by students using Seesaw (13 total). After the workshop, our team conducted a thematic analysis of our qualitative data sources, including audio transcripts, Seesaw activities, and prototype.

Results of thematic analysis of social wellness for early social media users

Through our discussion of wellbeing topics related to social media usage and identity formation, participants shared their early experiences using social media. The primary themes emerging from these discussions were 1) experimentation on social media, 2) sense of belonging, 3) self-care.

Affordances enabling experimentation

Participants described experiences experimenting with new apps as viewers of content, such as TikTok that grew in popularity in 2020 and that they tended to hear about through word-of-mouth. Participants reported rarely creating content. When they did, they were especially attuned to the comments they received. This feedback can have a lasting effect on the type of social media users they will become. They appreciated positive comments that boosts their confidence; they also mentioned feeling particularly vulnerable to mean comments. While the strongest influence for experimenting with social media was through friends, students in our workshop also discussed the pressure to experiment that they perceive while watching social media content, particularly when it came from online influencers.

Affordances enabling a sense of belonging

Participants described opportunities to explore different facets of their identity on social media. One student shared about how she really loves anime and she doesn’t have a community of friends who also love anime in school so she uses social media to connect with people in a larger community who share the same interest. With their close friends, students used many different types of applications, and most with their best friends. Snapchat was strongly associated with more intimate close friend communication. Specific features of Snapchat contributed to feeling more connected to friends such as maintaining streaks as a constant reminder to communicate:

“It kind of reminds me to talk to my friends…I don’t want to like lose my streak close to 200 and something and you end up snap trying them every day. And I also found that like I used to do it as much. But I found that actually helpful during quarantine to make sure that I’m talking to my friends.” P21, F.

Students also recounted the importance of validation about their content, especially coming from friends.

Since our workshop occurred during the pandemic, the sense of family and family bonds might have been stronger due to the time spent together in close proximity and these relationships were less mediated by social technologies. They mentioned that their parents played a large role in the control and safety of social media usage.

Self-care and social support strategies

Participants actively sought videos to boost happiness. Knowing places that they could reliably find content that boosts their emotional state is a method of resiliency and self-care that these students demonstrated.

“This video from YouTube […] is encouraging and for me I really like puns so this makes me feel happy. Also when I feel sad I like to see funny drawing.” P11, F.

They also mentioned ways in which they actively managed their exposure to certain audiences. For example, they would use explicitly private spaces such as private Stories on Snapchat. In contrast, they also described experiences with implicit privacy, such as YouTube, where the size of their audience limited their exposure.

They became aware of the psychological impact they can have on others. Students described a newfound sense of empathy resulting from our discussions.

“I learned about how important it is to be careful about what you say or it might put someone down” P8, F.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the daily rhythms around social media. As described by a workshop participant, she balances her time online with other offline activities.

“I feel like I’m doing more [social media during quarantine]. I don’t post a lot but I feel like I scroll through a lot more. And because there’s things I can do other social media so I try and get outside whatever I can.” P8, F.

Iterative design of Social sketch

We conducted an iterative design process over the 4 days of the workshop, to design a supportive social website for early social media users. Over the course of the 4 days, students provided ideas for the design of this website, based on our wellbeing discussions.

The website became Social Sketch, a social network to share pictures of drawings in a semi-anonymous and supportive environment. We describe next some of the core design decisions.

Prior research has found that anonymous platforms are particularly risky for teenagers, in fact our participants did not actively use anonymous apps. However, anonymity is a way to manage self-expression by choosing a username, or by toggling anonymity as needed, and can have benefits for self-discovery at a critical age of identity formation. Students reflected on the flexible use of anonymity and lack of engagement.

“I think that something you could do is make it so if you would like to post without anyone knowing it was you then but also make it so people could know it was you” P11, F.

We had also discussed the impact of likes and engagements through the workshop, despite the issues and interests in no engagement metrics, there was still some discussion about adding them. So instead of adding likes (an explicit action) we added view counts. Students expressed their desire to limit engagement metrics for wellbeing:

“you could post things without [worrying] about people judging you” P1, M.

Students suggested adding tags on posts and filtering mechanisms to see posts of most interest. These mechanisms contribute to behaviors they described using in existing platforms to manage self-care, and to feel a sense of belonging with individuals and groups with similar interests. Students also commented on personalization algorithms, which went beyond our rapid prototyping timeframe, but was able to be discussed and explored with the notion of tags. These curation mechanisms can facilitate self-care and help limiting information overload and distractions. On the topic of tags, they found them helpful especially as a way to reduce risk because they point to the things that you are interested in.

Participants also had ideas for improving the profile page with additional information including a profile picture (ex: could use a photo of your dog), a bio, links to profiles on other social media sites, and interests or “what their account is about”. We saw these early social media users already engaging in the understanding of personal branding.

Takeaways from the workshop

Overall workshop outcomes

Out of the 23 participants, 15 took both the pre- and the post-surveys. Girls reported increases in the importance of sharing about their abilities, achievements, and future career plans online and feeling of belonging in online communities. Girls reported an increase in their belief that they are good at computing and that learning about technology will give them many career choices. Overall, participants were less likely to think that computing jobs were boring. Girls’ self-esteem and sense of agency increased from pre-study to post-study. The most enjoyable activities involved guest speakers in ICT professions, testing iterations of the social media site, and identity exercises exploring career possibilities.

Roles in the cooperative design process

We found that the students in our workshop did not always take on the full innovator’s role that we set for them, due to lack of experience or functional fixedness, that is prior knowledge preventing them from expanding their creative thinking. For example, they tended to adapt the Seesaw prototypes to them as users rather than creators of the infrastructure, reverting to reconfiguration behaviors rather than innovation. It was difficult to distinguish them from their role as users, and customizing UI elements based on the content vs. the layout. This observation may be due to their stage as early social media users who are still navigating an ever-shifting digital landscape.

Honing in on student skills

Our dedication to supporting participants as design partners was also in helping train them to gain the necessary knowledge to be contributors. It is difficult to fully include middle school students in the design process of social systems due to the interdisciplinary and complexities involved. For example, understanding databases is a central technical component to building a multi-user system.

Remote format

Some of the positive aspects that emerged from our workshop were only possible because of the workshop structure: such as spending multiple days working on online projects together with a group of peers. The excitement and social proximity of this remote setting might inspire a different set of ideas than one developed in a shorter time, and may empower students differently than a classroom curriculum. We saw that some students started to participate more when other students had spoken, and they frequently bounced off of each other’s ideas.

Reference

For a more in-depth discussion and presentation of data, our complete paper is available at: Linda Charmaraman and Catherine Grevet Delcourt. 2021. Prototyping for Social Wellbeing with Early Social Media Users: Belonging, Experimentation, and Self-Care. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘21)